3

Nomad Migration in Central Asia

KAZIM ABDULLAEV

Institute of Archaeology, Samarkand

THE ETHNIC AND CULTURAL IDENTITIES AND MIGRATION ROUTES of Central Asian

nomadic tribes present one of the most disputed questions of those related to the

Kushans. The tribes appear in literary sources preserved mainly in Chinese chronicles

and in scarce references in the works of Greek and Latin authors. The migration of

Central Asian nomads, particularly into Transoxiana can be divided into two categories. The long ‘trans-regional’ route is ascribable to the Yuezhi migration from the

valley of Gansu, on the northern borders of China, to the territory north of the Oxus

River (Amu Darya), while the migration of tribes like the Dahae, Sakaraules,

Appasiakes, Parnes etc. can be classified as ‘local’ movements.

Strabo (XI, VIII, 2) gives a description of the locations of nomad peoples. ‘The

majority of Scythians, beginning with the Caspian Sea region, are called Dahae. The

tribes living to the east of them are the Massagetes and Sakas; the others are commonly known as Scythians, although each tribe has its own proper name. All of them

are nomads. Of these nomads, the best known are those who annexed Bactriana from

the Greeks, namely the Asii, Passiani, Tochari and Sakaraules, who migrated from the

other side of the Jaxartes near the regions of the Sakas and of the Sogdians occupied

by Sakas’. The second part of this information is important, but complicated at the

same time.

This fragment provides information about the territory north of Bactria, if we take

account of the fact that Strabo considered the River Oxus to be the border of the

regions now in modern Kashka Darya, Surkhan Darya and southern Tajikistan.

However, the last two territories are associated in scientific literature with northern

Bactria.

As experience of historic and archaeological investigations shows, however, the paramount goal in determining migration routes is the ethno-cultural identification of the

remains of nomad people along their routes. Decisions within this task depend on the

nature of the material currently available. The literary sources concerning this problem

have a contradictory character and insufficiently reflect the course of historic events.

Proceedings of the British Academy 133, 73–98. © The British Academy 2007.

�74

Kazim Abdullaev

The indicated geographic points have been the subject of discussion until now. The

localization of ancient regions and cities remains hypothetical. The analysis of literary information without supplementary material (in this case archaeological) leads

sometimes to conclusions far from the reality, such as those of Borovkova (1989).

Zadneprovsky (1997a and b) justly criticizes Borovkova’s localization of the Yuezhi on

the bank of the Syr Darya, but his own location of them in the Zerafshan valley is also

disputable. Finds of Kushan coins in this area are extremely rare, but their abundance

to the north of the Oxus shows that the Yuezhi settled there and created the core of the

future Kushan kingdom.

The events determining nomad migration in Central Asia are connected with the

history of the northern and western borders of Han China in the second century BC.

The Shiji (123), the Chinese ‘Book of History’ by Sima Qian, describes the conflict

between the powerful confederation of the Xiongnu and the Da Yuezhi. The latter

roamed between Dunhuang and the Qilian mountains (the Tian Shan of Gansu). In

176 BC, after suffering a crushing defeat by the Xiongnu and their leader Maodun, and

later, Laoshang, the Da Yuezhi moved west, crossed the kingdom of Da Yuan and

reached the banks of the Oxus. The Chinese ambassador and diplomat Zhang Qian

met them there in about 129/128 BC. He found them already settled on the right bank

of the Oxus. In this period they had not yet occupied southern Bactria (Da Xia), but

already had power over it. Besides this, it can be determined from the ancient source,

that the arrival of the Da Yuezhi on the banks of Oxus is impossible after this date. It

is clear that they passed some time in the lands lying between their initial homeland and

the banks of Oxus. Although the Shiji does not mention this, the gap is partially filled

by the Han Shu (Chronicle of the Han Dynasty): the first and most important event

which it relates is a Da Yuezhi attack on the Sakas. The second related event concerns

Kunmo (king of the Wusun), who pursued the Yuezhi, pressing them to move west.

Both events happened before the death of Shanyu, who reared Kunmo, that is to say

before 160 BC, a date too early for the conquest of Bactria (Pulleyblank 1966; 1970). As

for the Sakas, the same Han Shu chronicle (Han Shu, 96A, 5463) indicates that in the

period when the Chinese established contact with Kashmir (Jibin) by a Suspended

Crossing, they knew that the local rulers were Sakas, who had come from the North.

They were also told that the king of the Sakas had been forced out of his homeland in

the Pamirs by the Yuezhi.

Crossing Da Yuan, the Yuezhi found themselves to the north of the Oxus. It is interesting that the Chinese sources do not mention the other, no less important, river of

Central Asia, namely the Jaxartes (Syr Darya). In the opinion of some Chinese scholars, the Yuezhi tribes moved along the Yellow River and afterwards continued to

migrate westwards to the Yili River valley (Lu Enguo, 2002). Probably, by moving in a

westerly direction and crossing Da Yuan, the Yuezhi skirted the Altai and Turkestan

ranges around their northern extremities and found their way through Usrushana into

Sogdia (Abdullaev 2001).

�NOMAD MIGRATION IN CENTRAL ASIA

75

One of the most important sources of information on nomad migration in Central

Asia is Justin’s Prologue to Pompeius Trogus (prologue to book XLII), which states

that ‘the Asiani are kings of the Tochari and destroyed the Sacaraucae’ (Reges

Tocharorum Asiani interitusque Sakaraucarum). It is possible to conclude from this

extract that the Asiani and the Tochari were closely related tribes. What is more, it indicates that the ‘Asiani’ dominated the ‘Tochari’ (Reges Tocharorum Asiani). We can

identify the ‘Asiani’ with the ‘Kushans’ (von Gutschmidt 1888; Haloun 1937;

Bachhofer 1941; Daffina 1967), one of the leading tribes, which subsequently came to

power and created a great empire. It is noteworthy that Justin says that the Tochari were

ruled by the Asiani, while the Chinese sources identify them as the largest of the five

Yuezhi principalities. In my opinion it is very possible that the name Da Yuezhi in the

Chinese chronicles (for the early history of Kushans) was unknown in the West and

therefore was not mentioned in the ancient western sources. Whereas the Chinese

continued to call the tribes of Yuezhi by this name even after their migration, the

Greek and Latin authors gave them different names. In this case the identification

‘Asioi-Tocharoi ⫽ Da Yuezhi; Pasianoi; Sakaraukai’ (Daffina 1967, 52) is disputable.

The second part of Justin’s sentence is also important, for it gives information about

the destruction of the Sacaraucae. I propose that ‘the Asiani kings of the Tochari’

opposed the Sacaraucae, and that this confrontation took place between two completely different ethnic groups. One can also recall that Strabo’s list of the main tribes

who conquered Bactria from the Greeks included the Sacaraucae (Bailey 1985 and

Daffina 1967 are among scholars who have discussed the variant forms of this name,

Sakaraules and Sacaraucae, but only differing in the interpretation of the ethnonym

itself). Thus the second part of the sentence concerns the war of Asiani and Tochari

against the Sacaraucae. The latter were settled on the territory of Sogdia and Bactria

in the period before the arrival of the Yuezhi.

The Wusun problem and archaeological data

After being defeated by the Xiongnu, the Yuezhi migrated westwards. The first to clash

with them were the Wusun. According to the Chinese chronicles, the Wusun initially

inhabited territory in eastern Turkestan prior to being defeated by Xiongnu in 176 BC.

In about 160 BC, the Wusun moved to the area of Semirech’e following the same path

as the Yuezhi. According to this version of events the locally found Wusun cultural

remains must be dated no earlier than the second century BC. However, some investigators also attribute monuments of both earlier and later periods to the Wusun culture.

They identify as Wusun most of the necropolis remains of the third century BC to fifth

century AD in Semirech’e, Tian Shan, the valley of Talas, and at the foot of Karatau.

This interpretation is not sufficiently substantiated as it is based on the absence of

reliable chronology and a contradictory interpretation of literary sources.

�76

Kazim Abdullaev

The Chilpek, Buranin and Karakol necropolises were the first monuments of the

‘Wusun culture’ archaeologically excavated in the twentieth century by Gryaznov and

Voevodsky. They date no earlier than the third century BC to the first century AD, on the

basis of a study of the decoration, particularly of the gold rings and buckles. The presence of imported Chinese objects datable to the end of the third century BC has been

used to establish a chronology. The sewn buckles were compared with objects of

Sarmatian culture, as well as with material from the tumuli burials, kurgans of Shibe

and Katanda in the Altai, the latter dated to the second century BC to first century AD

(Voevodsky & Gryaznov 1938). However, later investigations showed that the Chilpek

group of burials belong to a later date, while the Buranin and Karakol finds could be

as early as the fourth century BC (Barkova 1978; 1979; 1980).

The greatest contribution to the study of Wusun culture was made by Bernshtam,

whose principle theory is based on the idea of the long continuity of the development

of the Wusun culture and not just the migration of this tribe in the second century BC.

Bernshtam introduced the term ‘Saka-Wusun’ to include cultural monuments of the

preceding period as well as the previous epoch. Monuments such as the Semirech’e and

Talas valley burials were attributed to this culture. They included ground-level tombs,

with a mound erected over them, in which the deceased was placed in an extended position with its head oriented to the West. The necropolis of Berkarin is the archetypal

monument of this kind. It includes two groups of burials belonging to two distinct periods: Saka (fourth to third century BC) and Wusun (second century BC to first century

AD). However, it has a wider chronological framework for additional objects of a later

period were also found here (Moshkova 1992, 27). Bernshtam (1952, 50) also identified

the necropolises and partial burials of Alamyshik and Jergetal and the necropolis of

Sokolovka and Jerges— dated by him to the second century BC to the first century AD

—as monuments of Wusun and Yuezhi type. The dating of the Sokolovka necropolises

was based on the analogies between the wood ceilings of its tumuli burials and the constructions of the Pazyryk burials. He dated the latter to the third century BC. However,

according to the latest data, archaeologists are inclined to date the construction of

Pazyryk — like the monuments of Shibe, Katanda and Berel — to the fifth to fourth

century BC. Consequently, the necropolises of Sokolovka must be identified as monuments of the Saka period. As for the Jerges necropolis, the date of the material

(pottery) found in it cannot yet be determined.

The remains concentrated in the valley of the Ili River and excavated by Kushaev

are associated with Wusun culture. Based on the peculiarities of the burial constructions and a study of the material, he identified three distinct phases: third to

second century BC, first century BC and first century AD (Kushaev 1963). But these

phases are only acceptable as a relative chronology, while the absolute chronology

remains undetermined.

In the Tian Shan mountains, the monuments of the Wusun period were explored by

Kibirov (100 burials in 19 necropolis). Based on the information in literary sources and

�NOMAD MIGRATION IN CENTRAL ASIA

77

interpreting the studied remains as Wusun, the author links them with the mass migration of the Wusun population under pressure from the Juyans. The monuments have a

wide chronological framework down to the fifth century AD (Kibirov 1979).

From the archaeological data one can sum up the situation as follows: the nomad

monuments are represented by several forms of burial construction which continued in

use over a long period. Some of them precede the Wusun arrival in the second century

BC and ‘present the remains of one people and belong to different periods of its historic

development’ (Kozhomberdyev 1975). Amongst the great quantity of monuments of

north-eastern Central Asia, one can only ascribe a certain number as the remains of the

Wusun culture (Mandel’shtam 1983, 47–8). At the same time there are no reliable signs

for determining this definitive culture. The graves of the Talas valley, Semirech’e and

Tian Shan are more probably linked with the tribes of nomads, i.e. the cattle-breeder

descendants of the Sakas.

One of the widespread types of burials in the nomad culture of Central Asia is the

so-called podboy, or tomb with an underground chamber and a side niche (alcove). The

chronological frame for this type of burial extends from the mid-first millennium BC to

the first half of the first millennium AD. The variations of certain details in the burial

construction and the character of the contents are linked to differences in landscape

and tribe. Podboy burials show such variations as the position of the chamber in relation to the entrance and the orientation of the deceased. Catacomb burials are distinguished by an entrance passage and the position of the catacomb itself: for example, in

one type the distinctive feature is the continuation of the entrance passage and in

another it is the perpendicular position of the catacomb in relation to the entrance passage. The question of ethnic attribution was posed by Bernshtam at the time of the

discovery of the Kenkol necropolis. Analysing the material of the burials (the arrowhead and pottery forms and the presence of a silk textile dated first century BC to first

century AD), he concluded that this type of burial was made by the Xiongnu.

However, this attribution was criticized by Sorokin (1954 and 1956), whose analysis of the remains demonstrated the local character of the culture. He also proposed an

alternative date for the Kenkol necropolis in the second to fourth century AD. Several

investigators considered podboy and catacomb necropolises as evidence of a local

culture of a population with certain imported elements (Moshkova 1992).

There were attempts to distinguish certain groups of these burials as characteristic

of different ethnicities. Zadneprovsky (1960, 137), for example, linked some of them

with the Yuezhi migration, particularly the necropolis with podboy type tombs.

However, this correlation is not supported by Chinese archaeologists such as Lu (2002),

when excavating podboy tombs and similar burial constructions discovered in China

(Daodunzi in Ningxia province in Northern China, Subeixi, Chawuhu III in Eastern

Tian Shan, Hamadun in central part of Gansu province) as they identify the Chawuhu

necropolis in particular as remains of the Xiongnu.

�78

Kazim Abdullaev

Podboy and catacomb necropolises are clearly present in Ferghana. Litvinsky (1972,

64–72) devoted some of his work to them. He traced elements of the Sarmatian culture

in these burials. In his opinion, the catacomb burial construction forms arose in the

Bronze Age and have parallels with the Saka kurgans in Besshatyr and Semirech’e, and

the kurgans of the Lower Syr Darya (Chirik-Rabat).

The burial monuments of Sogdia

The greatest contribution to the study of the tumuli necropolises of the Samarkand

and Bukhara regions has been made by Obel’chenko (1961). In the Samarkand area, he

excavated the Agalyksay, Akjartepa, Mirankul and Sazagan necropolises. In the

Bukhara region he investigated the necropolises of Kalkansay, Kyzyl Tepe, Kuyumazar,

Lyavandak, Shakhrivayron, Khazara and Yangiyul (Fig. 1). Amongst the rich diversity

of burial constructions, one can distinguish three main types: podboy, catacombs and

graves. He associated the podboy burials with the Yuezhi migration, but the other two

with the Sarmatian culture of the southern Urals and the lower Volga. However, the

archaic appearance of a catacomb burial in the Kuyumazar necropolis (kurgan no. 3,

near the Soinov mound) gave rise to some doubts about its strange character. The sub-

Figure 1. The Map of the main Nomad monuments in Sogdia and Bactria. 1 Kalkansay; 2 Yangi

Kurgancha; 3 Akjar; 4 Aksay; 5 Sazagan; 6 Mirankul; 7 Agalyk; 8 Kuyumazar; 9 Kiziltepa;

10 Shari Vayron; 11 Khazara; 12 Babashov; 13 Kokkum; 14 Aruktau; 15 Tulkhar;

16 Rabat-I, II, III; 17 Airtam.

�NOMAD MIGRATION IN CENTRAL ASIA

79

sequent discovery of the second millennium BC Zamanbaba necropolis in the

Zerafshan valley confirmed that this form of burial was of local origin. The

Zamanbaba necropolis included burials with an entrance passageway and a catacomb

(Gulyamov et al. 1966, 119–29). The presence of such burials during the late Bronze

Age (ninth to eighth century BC) has also been attested in southern Tajikistan.

Obel’chenko’s conclusion that ‘the participation of the tribes of the Sarmatian

world in the crushing defeat of the Graeco-Bactrian kingdom gives a somewhat different nuance to the Chinese Chronicles’ (Obel’chenko 1992, 230) is, however, disputable,

as the theory of a Sarmatian invasion of Central Asia in the second to first century BC

is not acceptable to other scholars (Mandel’shtam 1974; Zadneprovsky 1997b, 77;

Abdullaev 1998a and b, 24–5).

In the late 1980s several kurgans near the village of Orlat in the Samarkand region

were excavated. The site became well known thanks to some remarkable bone plaques

depicting various scenes of a battle, hunting and zoomorphic motifs. The catacomb burial construction type at Orlat, i.e. with the chamber at the axis of the entrance passage

mainly oriented north-south, is similar to that at other Samarkand region necropolises,

although a certain number have a west-east orientation. The burial finds include pottery

and weapons: swords, daggers, arrowheads of a nomadic type, bone appliqués for bows

etc. Pugachenkova (1989, 122–54) links the Orlat necropolis to the Kangju tribal group

who held the territory to the west of Samarkand in the second to first century BC.

In the same region of Samarkand (Koshrabat district), the excavation of the Sirlibaj

Tepe kurgan revealed burials of various types and periods. In one of them, there was a

catacomb located perpendicular to the axis of the entrance passage. The corpse was

placed in an extended position, with the head oriented to the south, on a bed of twigs

on the floor. A second burial was located in line with the axis of the entrance passage,

which had five steps, with the remains of a coffin in the catacomb. A third burial, of

podboy type, was discovered in the sub-burial construction. Its niche was located in the

north-western wall of the grave. The head of the corpse was oriented north-east.

Finally, a fourth burial was a grave with an entrance passage (the body was missing).

The entrance passage and the grave are oriented on the same north-west to south-east

axis. In the opinion of the excavators, this is the earliest of the excavated burials. It has

analogies with the finds of the southern Urals (fourth century BC) and the necropolis

of Tagisken in the eastern Arals (fifth to fourth century BC). The podboy burial is similar to that of the Orlat kurgan no. 9, dated first century BC to first century AD (Ivanitski

& Inevatkina 1988).

Burial monuments of the nomads of northern Bactria

One of the most important studies of the nomads of Central Asia was the discovery

and research undertaken principally by Mandel’shtam at the necropolis in southern

�80

Kazim Abdullaev

Tajikistan. His investigation of a great quantity of podboy type burials, mainly in

Bishkent valley (Tulkhar, Aruktau and Kokkum (Fig. 1)) led him to the conclusion that

the culture represented by these necropolises was that of the people who crushingly

defeated the Graeco-Bactrian kingdom and ultimately established the Kushan Empire.

The detailed study of the finds of these necropolises is given in the works of

Mandel’shtam (1966, 1968 and 1975). Another nomad necropolis at Babashov in

Turkmenia, also excavated by Mandel’shtam (1963), closely resembles the culture represented by the Bishkent valley burials.

Nomad monuments survive to a lesser extent in Uzbekistan, because the development of land for cultivation included the area of foothills where necropolises were

located, so that they have been destroyed. Such destruction has also occurred in more

urban areas. Some idea of what has been lost is provided by the site of Airtam, 18 km

to the east of modern Termez. Apart from the remains of monumental buildings decorated with stone reliefs, burials have been found here which can be linked to nomad

culture. The construction and funerary finds of the Airtam burials are very similar to

those of the Tulkhar necropolis (Turgunov 1973, 64–8). Two types of burials are found

at the Airtam necropolis: a rectangular grave and a podboy (oriented north-south). The

finds included a double-blade dagger (35 cm in length), three iron rings and an arrowhead. The pottery and other finds from the funerary complex show close analogies with

the material from Tulkhar, Aruktau and elsewhere. The necropolis of Airtam can be

dated to the second to first century BC.

As mentioned above, the nomad monuments of Uzbekistan have been completely

destroyed. One of them, the Rabat I necropolis in the Baysun district of Surkhan Darya

region (Fig. 2), was situated within the site of Payon Kurgan, a fortress of the nomad

Figure 2. Necropolis Rabat I. Modern and ancient tombs.

�NOMAD MIGRATION IN CENTRAL ASIA

81

migration period (Abdullaev 1999). This remarkable monument— part of a huge

necropolis on the upper terrace of the Akjar River — extended from north to south for

a distance of about 1 km. It was discovered by accident during preliminary digging for

modern construction work. It was almost completely destroyed and the site is now covered by the vegetation and buildings of the modern village of Payon (which means

‘lower’ in Persian). Only ten tombs could be traced and in only one a skull with circular deformation was found. The archaeological material from the tombs— different

weapons (arrowheads), a mirror and jewellery — is very similar to the finds from

Tulkhar, Aruktau and other necropolises of the Yuezhi type.

The Rabat II necropolis was discovered much later (Fig. 3). Evidently it was a continuation of Rabat I and was aligned in the same north-south direction. Here also,

following the complete destruction of the surface remains, we traced and excavated

ten tombs with some funerary material. The pottery collected on the surface (after the

destruction of the site) belongs to the Kushan period and is dated first to second century AD (Fig. 4). The presence of piles of large stones suggests that the tombs were

placed inside a stone enclosure which had been dismantled during the modern

destruction of the site.

The Rabat III necropolis is situated about 1 km south-west of the village of Rabat,

at the foot of the Baysuntau mountain (Fig. 5). It covers an area of about 0.5–0.6

hectares. On the surface, the rectangular or oval stone enclosures of the tombs are

clearly visible. Most of them appear to be oriented north-south, but the site has not yet

been studied.

The most representative excavated site of nomad type in Afghanistan is Tillya Tepe,

where the tombs contained many remarkable objects in gold, silver, bronze, stone, and

Figure 3. Necropolis Rabat II (first–second centuries AD). General view after destruction.

�82

Kazim Abdullaev

Figure 4. a (top): Plate with incised ornament from Rabat II. b (below left): Two handled pot

(amphora shape) from Rabat II, first–second centuries AD. c (below right): Goblet covered with red

slip from Rabat II, first century BC–first century AD.

so on. For this complex, there are good chronological indicators— such as coins —

which provide a relatively short time-frame of the first century BC to first century AD.

But its ethnic identity is still disputed. The excavator, Sarianidi (Sarianidi 1985 and

Sarianidi & Koshelenko 1982) considers it to be Yuezhi. The character of the finds is,

however, notably mixed, for they include clear motifs belonging to the artistic culture

of Pazyryk burials, as well as certain Chinese artefacts, and Saka elements that indicate a local tradition with strong Hellenistic influence. In any case, we have here an

amalgamation of artefacts from Siberia to the Graeco-Roman world.

�NOMAD MIGRATION IN CENTRAL ASIA

83

Figure 5. Rabat III. General view of the Necropolis.

Nomad city-sites

An interesting aspect of nomad migration is the transition period from nomadism to a

sedentary way of life, that is to say, the development of urban culture, the establishment

of cities and the formation of a state, such as the Kushan state, for example. It should

be noted that this process has not been recorded in the literary sources and is inadequately defined by the archaeological sites. The temporary nature of nomad dwellings

allowed them to move easily over long or short distances in search of good pastures and

camps. This usual process of migration, dictated by a way of life, is known to a certain

extent from ethnological data. Of what does a nomad city comprise? This question has

not yet been addressed by scientific literature or archaeological investigations.

Chinese sources make special note of the capital of the Heavenly Empire, calling

it jingshi, which means, according to Bichurin ‘mountain army’, that is ‘people’,

because until the beginning of the Christian era, there was one military estate in

China, and for the residence of the Emperor they chose the high banks of the Yellow

River. The name jingshi applied only to the Chinese capital. For the capitals of other

states they use the name du, meaning a residence (Bichurin 1950, II, 149, note no. 4;

[editors: the etymology of jingshi proposed by Bichurin is more closely associated

with later usages of the term, which would be better interpreted from ancient usage

as the ‘king’s palace district’, as the character for jing shows a tall building and is

thought to represent the king’s palace, rather than a hill; shi means a large group of

�84

Kazim Abdullaev

people, and hence the army, but in the context of jingshi the people are more likely to

represent the people living around the king and hence the district around the king,

Karlgren 1957, nos 559 and 755].

All three Chinese sources (Shiji, Han Shu, Hou Han Shu) mention another type of

city (or capital), by adding the ending cheng— for example, Jianshi cheng or Lanshi

cheng— meaning ‘surrounded by a wall’. The first to pay attention to this detail was

Enoki, whose translation was used by Narain (1957, 129–30). Although the interior

structure of the city remains uncertain, nevertheless, it is noteworthy that an important

sign of a city was the wall surrounding it. This fact is especially appealing in that

the cities mentioned in the sources of Han epoch belong to nomad states. As noted

above, the term cheng is used for Jianshi and Lanshi. However, the same source, the

Han Shu, when listing the capitals of the five principalities (xihou) formed after the

settlement of numerous tribes in Central Asia, does not use the term cheng.

If the sources record a concept of the city cheng as fortified, that is enclosed by a

wall, then that can be interpreted as meaning a traditional, ancient Central Asian city

complete with citadel as, for example, Dalverzin Tepe. It does not necessarily mean a

type of nomad city.

It is logical to expect the existence of a transitional form of city between the two

types. The discovery of Kala-i Zakhoki Maron in the neighbourhood of the modern

city of Karshi (the capital of the Kashka Darya region) is a clear example of just such

an archaeological site (Fig. 6). The initial, most striking impression is the huge size of

this site. Its first investigator, Kabanov (1977), described it as ‘one of the most extensive sites of the oasis— the ruins of an ancient fortification and citadel, located at the

south-eastern extremity of Nakhsheb’.

Kala-i Zakhoki Maron is square in form with sides 400 m in length. The site consists of three concentric terraces, ‘gradually rising to the centre’. The width of the exterior rampart is 30 m and the height 7 m. The exterior sides are steep and the interior

ones more sloping. Kabanov (1977, 47) thought there were only two ramparts, but

Masson (1973, 20–30) identified a third of greater dimensions, also square, with sides

1.5 km in length. Further archaeological investigations of the site confirmed the presence of the third rampart. The archaeological context suggests that Kala-i Zakhoki

Maron was built in the second to first century BC. The remains of houses in the area

adjoining the ramparts (wall I and II) are of a later period (Turebekov 1981, 9–10).

A remarkable peculiarity of this site is the absence within the fortification — in the

extensive area between the citadel and the city walls — of any remains of buildings. This

peculiarity is noteworthy particularly if we take account of the huge expanse included

by the third city wall. If we admit that it formed a cohesive part of the structure of the

site —a proposal which is confirmed by the archaeological evidence— then the vast

dimensions of Kala-i Zakhoki Maron (1.5 km2) mark it as the largest site in the region,

surpassing even such examples as Afrasiab (Koshelenko 1985, 278). What is more, both

the plan and structure of this site are unusual. The closest analogies to the plan of

�NOMAD MIGRATION IN CENTRAL ASIA

85

Figure 6. Kala-i Zakhoki Maron. Plan of the site, second–first centuries BC.

Kala-i Zakhoki Maron are found at the sites of Shakhrivayron, in the Bukhara region,

and Janbaskala in Khwarezm (Tolstov 1948, fig. 29a; Turebekov 1981, 9–10).

Ancient literary sources, especially the Chinese chronicles, provide some information on the traditional cities of Central Asia, but there is nothing about the existence

of the ephemeral settlements of migrating nomads, which must have appeared and disappeared at the flourishing agricultural oases on the endless expanse of the steppes. We

can glean some idea of migration settlements from later sources, for example, the fragmentary preserved descriptions of European travellers who undertook long voyages to

the courts of nomad kings, for instance, to Orda of Tataro-Mongol. So in the colourful description by Guillaume de Rubrouck (XIX, 213) of the Mongol king Batu, he

gives the following information on the organization of the court:

When I saw Batu’s court, I was surprised because his own houses appeared to be like a great

city stretched out, and surrounded by people on all sides as far as three or four leagues. And,

as among the Israelites each knowing where to set his tent around the Tabernacle, so they all

knew which side of the court they should set their houses. So the court is called in their language orda, which means ‘middle’ [old Turkic orta ⫽ middle, centre], because it is always set

in the middle of the people, but no one is positioned to its South, as it is the side onto which

�86

Kazim Abdullaev

the doors of the court open. But to right and left the people establish themselves as they wish,

according to the lie of the land, so that they are not immediately in front or opposite the

court.

Ethnographic and archaeological investigations in Central Asia show that ‘a considerable portion of the nomad sites contain no sign of any permanent buildings. It indicates that part of these former cities were occupied by yurts (nomad tents) evidently set

out in quarters like later and even modern cities’ (Viktorova 1980, 59). A similar type

of city-site has been excavated at New Sarai on the Volga, where the house of a wealthy

man with a paved yard has been unearthed (Fyodorov-Davydov et al. 1960, 71). In the

area in front of it, yurts were found. It is interesting that even now in urban environments one can still see the combination of permanent dwellings and nomad tents, both

in rural areas and in cities, for example, Ulan Bator (Schepetil’nikov 1960 and Maydar

1971). So this ancient tradition has been preserved through the millennia to remain a

characteristic sign of the cities and settlements of former nomadic peoples. Even till the

present day, the stock-breeding population in the mountain villages of Uzbekistan’s

Surkhan Darya and Kashka Darya regions still place their yurts beside their modern

houses.

All these examples cited above provide substantial evidence for the origins of the

nomad city and as a prototype we propose the archaeological site of Kala-i Zakhoki

Maron. Very likely, the remains preserve the original plan of a single archaeological

site, in spite of the evidence of later dwellings in certain parts of the city. According to

the archaeological context, this city was built in the second to first century BC and can

be chronologically linked directly to the migration of the nomad tribes mentioned

above.

So, one can suppose that in this case we have a typical nomad city with a citadel in

the centre and divided by streets in earlier times into quarters filled with yurts (tents).

The erection of the fortification wall demanded a colossal workforce and the means for

building on such an enormous scale. These resources could have been supplied by using

the local population as forced labour to erect the city wall. In all probability, the walls

of captured cities were not always completely destroyed, but on the contrary, were

reused by the nomads for their own defences. The archaeological evidence from the

walls of Ai Khanum confirms this supposition (Leriche 1986, pl. 14).

Here in the ‘lower city’, in trench no. 1, during excavation of the fortification wall,

it was discovered that the wall had been repaired. It was strengthened with soil that had

been taken from the moat which surrounded the wall. It is interesting to note that there

was no connection between the re-fortified wall and dwelling complex. What is more,

within the walls of the former city, burials of nomad type were discovered. Does this

testify to the preservation and function of a fortification system after the destruction of

the city? In this case, did it protect the nomads and their temporary camp within the

destroyed city? I think, in this case, the answer can be yes.

�NOMAD MIGRATION IN CENTRAL ASIA

87

Images of nomads in figurative art

When it is a question of nomad peoples, the task of cultural identification becomes

complicated because of the absence of certain important elements that are characteristic, for example, of an urban population. The principal remains of the nomads are

funerary edifices that have been given a detailed classification and typology in scientific

literature. However, as the extensive research of Central Asian archaeologists has

shown, the study of funerary monuments does not give sufficient information for the

ethnic attribution of one or other tribe (Litvinsky 1972, 71–2). Many types of burials

and funerary constructions co-exist chronologically. The archaeological material presented mainly by funerary utensils also sometimes has a universal appearance (for

example, ornaments, utensils, armour, and so on). These funerary objects are termed

‘universal’ because they represent the common types and forms of the objects that constitute a part of the archaeological complexes of various ethnic groups but are found

spread over a wide area in certain chronological frames, so that they are often used for

the dating of archaeological and cultural complexes. For the clearer identification of

nomad remains, it is necessary to use a combination of different sources of data from

archaeology and other applied sciences. However, even such methods do not give an

exhaustive answer to the various disputed questions of Kushan archaeology. Probably,

in this instance, it is necessary to use other sources of information that could perhaps

help reveal certain aspects of nomad culture. To such a category belong the objects of

figurative art. They are, usually, part of a funerary complex and accompany the

deceased as prestige objects. Their relative rarity in burial complexes belies their

capacity for supplying useful information.

The objects of art representing nomad images can be divided into two categories.

The first belongs to funerary monuments; the second forms part of the interior decoration (relief or wall painting) of cult or secular buildings. The compositions mainly have

a secular character: battle scenes, hunting or other related subjects provide information

on the contacts between the steppe nomads and agricultural zones or oases.

It seems that the nomad way of life of does not itself presume to have such a category of material culture as architecture, although certain elements of it, for example,

burial constructions, demonstrate a good knowledge of building techniques (as can be

seen in the tumuli burials of the Altai). On the other hand, the construction of transportable dwellings also demanded the experience of spatial decisions. In the absence of

reliable sources, the interior design of nomad dwellings can only be reconstructed from

modern ethnographic data. The investigation of certain burials that probably represent

a model of a real nomad dwelling can also provide some information.

The objects of art are sufficiently diverse and embrace different aspects of social

life. They provide information on armour (and to some extent on military tactics),

dress, hairstyle, details of domestic life, religion, mythology, anthropology, and so on.

Identifying the find-spots of objects that closely resemble each other helps to trace the

�88

Kazim Abdullaev

routes of nomad migration and determine more precisely the areas of nomad settlement. So, for example, we can compare the representations on the bone plaques from

the Orlat necropolis in the Samarkand region with the fragment of a bone plaque

found in Kuyumazar necropolis in the Bukhara region (Figs 7 and 8). The similarities

between them are not, evidently, accidental.

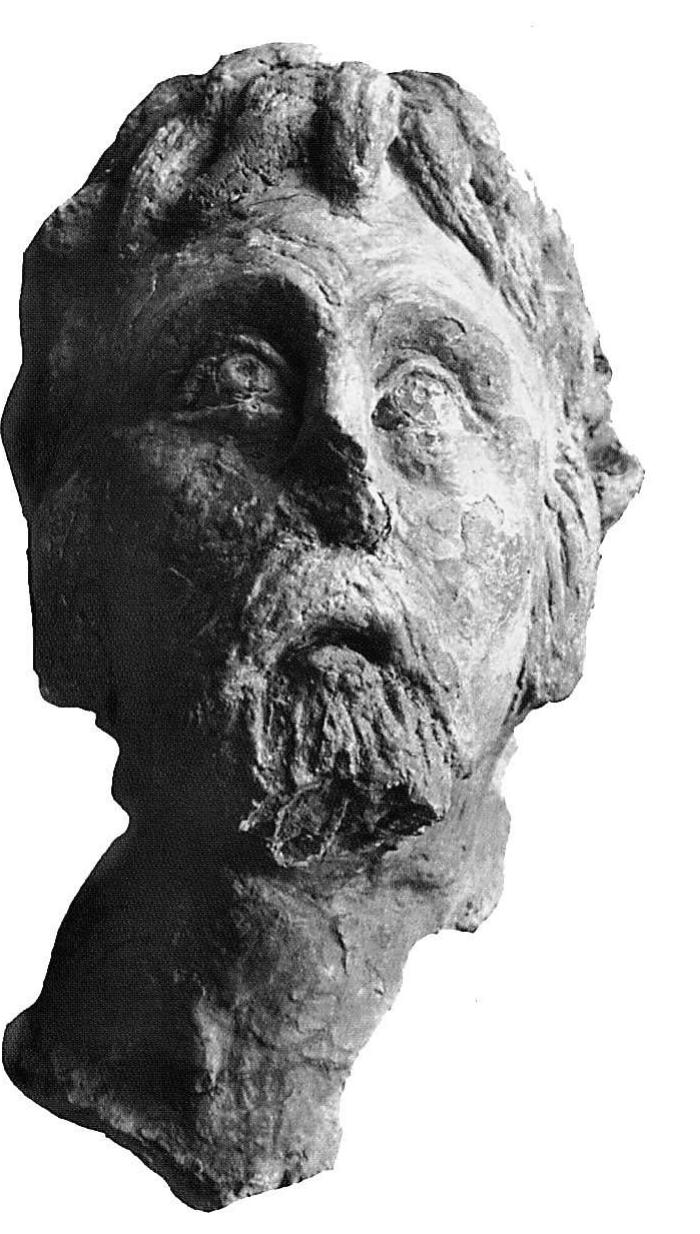

Figure 7. Bone plate from Kuyumazar Necropolis. Bearded man.

Figure 8. Orlat. Bone plate with representation of a battle scene.

�NOMAD MIGRATION IN CENTRAL ASIA

89

On the Kuyumazar bone plaque we have an abstract depiction of a male figure. His

head is in profile; the body in frontal position. He has short hair and a young face without moustache but with a beard. The beard is primitively modelled in straight parallel

lines. His dress is interesting, with a V-neck and ornamented with crosshatched lines to

resemble the armour of a warrior. The armour on the Orlat plaques is more precisely

depicted, but the representations of hairstyle and beard have close analogies with the

Kuyumazar example. Certain figures in the Orlat plaque of a battle scene have pointed

beards with or without a moustache. In the hunting scene, a figure in the lower section

of the composition has a pointed beard, no moustache and short hair. Such a beard is

characteristic of a series of art objects that appear to be from Sogdia. The knights in

chain-mail armour have analogies in the Khalchayan reliefs depicting a battle of the

Yuezhi against a Saka tribe (probably the Sakaraules). Apart from the chain-mail

armour worn by the heavy cavalry of the enemies of the Yuezhi, the other characteristic sign of these warriors is long side-whiskers. This detail is typical of the portraits on

early Sogdian coins representing a ruler on the obverse and an archer on the reverse.

On the right bank of the Oxus, lies the remarkable site of Khalchayan, with its

reliefs showing images of these nomads. These reliefs are one of the most famous examples of pre-Kushan art in Central Asia. Pugachenkova (1966; 1975) interpreted the

main scene on the reliefs as a triumphal procession of the victorious tribes of the

Yuezhi. She also identified the figures (based on a male head with moustache and diadem) with the Heraus clan. However, the numismatic finds, which suggest the succession of the Heliocles I imitations by the Soter Megas issues in Northern Bactria, did

not include any coins of this ruler (Rtveladze & Pidaev 1981). Some figures and some

fragments of the Khalchayan complex (the horseman shooting an arrow, the figure

with captured armour, the horse’s hoof treading on armour etc.) illustrate a battle

between the Da Yuezhi and other nomadic tribes, as proposed by Bernard (1987,

758–68) and developed by him with Abdullaev (Bernard & Abdullaev 1997; Abdullaev

1995a). There are some figures in the reliefs which are distinguished by their expressive

character. Some of them were identified by Pugachenkova as satyrs and demonic creatures. Indeed these expressive figures with side-whiskers differ greatly from the tranquil

and majestic faces and poses of the Yuezhi depictions. The Bactrian artist treated the

images of his enemies in a grotesque manner, also characteristic of Chinese art (GrumGrjimaylo 1928). We think it is possible to identify all these grotesque personages with

long side-whiskers as enemies of the Yuezhi and relate them to the Sakaraules mentioned above. Iconographically they are very close to the representations on the early

coins with the archer on the reverse (Abdullaev 1995b, figs 7–8), which have mainly

been found in the regions of Samarkand and Bukhara. We thus have distinguished two

different and antagonist ethnic groups in the Khalchayan reliefs. They are represented

in Khalchayan in a time of confrontation. Naturally these scenes of the Khalchayan

figurative complex reflect a historical event which happened in the second half of the

second century BC. In any case it was before the visit of the Chinese diplomat Zhang

�90

Kazim Abdullaev

Qian in 129–128 BC (this date is corrected from my previous erroneous dating of 123

BC, Abdullaev 1995a, 155). Have we any archaeological layers belonging to period of

the Sakas, who occupied the northern lands of Bactria before the arrival of the Da

Yuezhi?

Clearly any layers of the Saka period must be situated immediately underneath the

Yuezhi layers. These have been found at Dalverzin Tepe, one of the main Kushan sites

in southern Uzbekistan (Belyaeva 1978). Two remarkable fragments of wall paintings,

from a layer which preceded some substantial repair work after the destruction of a

building, are particularly interesting (Belyaeva 1978). Indeed, the archaeological context attests here the presence of a population just before the Yuezhi arrival in northern

Bactria. The polychrome painting fragment from Dalverzin Tepe shows a helmeted

warrior (Abdullaev 1995a, 154–5) who resembles certain figures from Khalchayan.

Iconographically, images of an armoured warrior can be linked to representations on

the coins of Tanlismaidates, who was a local ruler. The majority of these coins have

been found to the west of Balkh.

We have thus examined some of the figures on the Khalchayan reliefs. Others—

with a demonic expression and a very distinctive hairstyle with long side-whiskers — are

paralleled in terracotta plastic art. We have at present several images resembling the figures of Khalchayan. One of them was found in a second to first century BC layer at the

site of Old Termez (Fig. 9). It is a moulded yellow clay figure in high relief with a flat

back, representing a male head with large ringlets and long whiskers, originally

misidentified by the excavator as a female (Pidaev 1987, 89). There are vertical lines

clearly identifiable as chain-mail armour on the neck.

The second terracotta figurine represents a bearded male figure seated on a low conical chair. It was found at Kampyr Tepe (Surkhan Darya region) in layers of the second

to first century BC (Fig. 10). The head was moulded while the hand was modelled in a

primitive way. The figurine depicts one of the members of the ruling class of nomads,

who in the second half of the second century BC conquered Bactria, shattering the once

great Graeco-Bactrian kingdom (Abdullaev 1995b, 176–7).

The third example is a hand-modelled figurine found at the site of Erkurgan (a

major site near modern Karshi, in the Kashka Darya region to the south-south-west of

Figure 9.

Old Termez. Terracotta figurine with representation of a warrior, second–first centuries BC.

�NOMAD MIGRATION IN CENTRAL ASIA

Figure 10. Kampyr Tepe. Terracotta figurine

with representation of a warrior, second–first

centuries BC.

91

Figure 11. Erkurgan. Terracotta figurine

with representation of a warrior, second–first

centuries BC.

Samarkand) (Fig. 11). The representation is treated in a schematic manner, but there

are some significant elements in its iconography. The terracotta armoured figurine has

a high collar and long side-whiskers just like certain of the Khalchayan figures. It is

dated stratigraphically to the second century BC. It is interesting to note that the archer

figure on early Sogdian imitation coins has armour with a similar high collar

(Mitchiner 1976, 5, 432, no. 652)

Thus, both in the archaeological layers and in the figurative complexes, we can distinguish two different images of the northern Bactrian population. The Khalchayan

reliefs show us the scene of a battle between the Da Yuezhi and Saka (Sakaraules,

Sacaraucae). It is possible to attribute the Khalchayan reliefs to the first century BC

archaeologically, but the historical events reflected in them belong to an earlier period,

i.e. to around the middle of the second century BC. In general, one can say, that the

Khalchayan complex represents a bridge between the Hellenistic art of Bactria and the

Hellenized Kushan Art.

In this connection, an engraved gem (intaglio) from Samarkand Museum depicting

an image closely resembling the above personages is interesting. Its very early Sogdian

inscription was first noted by Borisov (1963), who read it as ‘f-r-n’ (farn, parn).

�92

Kazim Abdullaev

Certain iconographic peculiarities of this image should be noted. The figure has a

European appearance with a straight nose, a wedge-shaped beard, no moustache and

short hair. The hairstyle resembles that on some figures from ancient Sogdia. A similar

beard and no moustache can be seen on the bone plaques from Orlat, dated to the

second to first century BC. The figures on these plaques we identify with the tribes

surrounding Samarkand, namely the Sakaraules (Abdullaev 1995a and b).

Early Sogdian coins with the name Hyrcodes and an archer on the reverse (dated

130 BC to first century BC by Mitchiner 1976, vol. 5, 436, type 669) have a certain similarity in the modelling of the face. The personage on these coins has the same beard

and hairstyle, the head turned to the right. This is interesting, especially the coin cited

by Zeymal’ (1983, pl. 31 no. 8). Another feature in common is dress, which is depicted

with oblique lines to form a V-shaped neck. One can suppose that the figure on the gem

represents the portrait of a local ruler, who appears to be ethnically close to the rulers

depicted on early Sogdian coins, dated by Zeymal’ (1983, 269) to the second to first

century BC. The gem from Samarkand Museum can be dated to the end of the second

century BC to first century AD (Fig. 12).

Conclusion

Literary sources recount how the Yuezhi on their long journey from the valley of

Gansu met different peoples. The first were the Wusun. After their defeat by the Wusun

in the region of Semirech’e, the Yuezhi migrated further in a westerly direction. Passing

through Da Yuan, they reached the region between the two rivers of Amu Darya and

Syr Darya. Here, north of the Oxus River, they found another tribe already settled for

some time, whom we can hypothetically identify as the Sakaraules.

Figure 12. Samarkand Museum. Engraved gem

(cornelian), first century BC–first–second centuries

AD. Portrait of a governor.

Figure 13. Early Sogdian coin. Portrait of a

ruler, second–first centuries BC (?).

�NOMAD MIGRATION IN CENTRAL ASIA

93

This tribe is linked with the culture of the archaeological monuments of lower Syr

Darya and is placed in eastern provinces of Khwarezm (Choresmia). Tolstov (1948,

243) and von Gutschmidt (1888, 58 and 70) identified them with the Kangju.

In approximately the third to first half of the second century BC, these tribes

migrated in a southern direction and settled around the Samarkand and Bukhara

oases. In all probability, one can connect the representatives of the culture of the Orlat

kurgans (tumuli) with the tribe of the Sakaraules, who dwelt in former times in the

region of Kangju. If we follow this scheme further, the territory of the Sakaraules

accords with the description in Strabo, who locates them as coming originally from the

region beyond the Jaxartes river.

Numismatically the Sakaraules can be associated with early Sogdian coins depicting a ruler in profile on the obverse and an archer on the reverse (Fig. 13). The other

group that hypothetically can be related to this period or earlier is the early imitation

of Antiochus I’s coins with a horse’s head on the reverse. Geographically both types are

concentrated around Sogdia, including the Bukhara region. But chronologically, it

seems very probable that the tribes around the Bukhara oasis had already gained their

independence in the Seleucid period, while Sogdia and Bukhara itself became free from

Greek power during the reign of Euthydemus I (Bopearachchi 1990). Numerous imitations of his coins testify to this. We have another imitation of Greek coinage, namely

of Eucratides’ coins. Imitations of his obols are clearly local to the region of southern

Tajikistan and partially in Uzbekistan. It is confirmed by Strabo’s information on the

Parthian annexation of the Bactrian territories (i.e. the satrapies of Aspiona and

Figure 14. Khalchayan clay sculpture, late second–first centuries BC.

�94

Kazim Abdullaev

Turivu). A more complicated imitation is the so-called ‘barbarized’ Heliocles coins. The

finds of these imitations are mainly local to the modern Surkhan Darya region, south

of Tajikistan and to the south of the Oxus river. The variety of imitation types supposes long continuity and circulation of these imitations in certain areas. Zeymal’

(1983, 110–28) gives a detailed typology of the Heliocles imitations. Amongst the 7

types of imitation proposed by him, the first two (I and II) hypothetically can be associated with Saka coinage. However, it is a proposition that needs to be argued in

more detail. The problematic typology, chronology and attribution of the Heliocles

imitations is beyond the scope of this paper.

Very likely the Khalchayan reliefs demonstrate the historical event when the Yuezhi

confronted the Sakas, probably the Sakaraules, and in defeating them, established their

own power over the territory to the north of the Oxus (Figs 14–16). Later they subjugated the region to the south of the Oxus— the kingdom of Da Xia of the Chinese

chronicles— and still later, they moved further into the Indian subcontinent.

Figure 15. Khalchayan clay sculpture, late

second–first centuries.

Figure 16. Khalchayan clay sculpture, late second–

first centuries BC. Representation of a warrior.

�NOMAD MIGRATION IN CENTRAL ASIA

95

So, according to the archaeological data, one can suppose that the nomad tribes

gathered round the Bukhara oasis in its western and north-western parts were, in the

majority, local. Similar tribes populated the east and north-eastern part of Margiana.

It is very possible that those tribes moved to the Surkhan Darya and Amu Darya

plains, and further that they were forced out by the Yuezhi arrival from Siberia and the

Altai. There is evident iconographic similarity between certain Khalchayan figures and

the portraits on the obverse of the Sogdian coins with the archer reverse. In particular,

the long side-whiskers appear on both the coins and on the sculptural representations

of Khalchayan (Abdullaev 1995a).

References

ASGE

BSOAS

CIAA

CRAI

IAN Turk SSR

IMKU

JRAS

KSIIMK

MIA

RA

TKAEE

VDI

ZDMG

Arkheologicheskie Sbornik Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha, Leningrad.

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, London.

Circle of Inner Asian Art, London.

Comptes rendus de l’Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres, Paris.

Izvestiya Akademy Nauk Turkmenskoy SSR, Ashgabat.

Istoriya material’noy kul’tury Uzbekistana, Tashkent.

Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, London.

Kratkie soobscheniya Instituta istory material’noy kul’tuey, Leningrad.

Materialy issledovany po arkheology, Moscow, Leningrad.

Rossiyskaya Arkheologia, Moscow.

Trudy Kirgizskoy arkheologo-etnograficheskoy ekspeditsy, Moscow.

Vestnik Drevnei Istory, Moscow.

Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenlandischen Gesellschaft, Leipzig, Wiesbaden.

ABDULLAEV, K. 1995a. ‘Nomadism in Central Asia. Archaeological Evidence, second–first century BC’. In A. Invernizzi (ed.), In the Land of the Gryphons. Papers on Central Asian Archaeology

in Antiquity, Florence, 151–61.

ABDULLAEV, K. 1995b. ‘Armour of Ancient Bactria’. In A. Invernizzi (ed.), In the Land of the

Gryphons. Papers on Central Asian Archaeology in Antiquity, Florence, 163–80.

ABDULLAEV, K. 1998a. ‘Nomady v iskusstve ellenisticheskoy Baktry’, VDI, 1998.1, 83–92.

ABDULLAEV, K. 1998b. Sarmary ili Yuechzi ? (K voprosu o kul’turnoy identifikatsy nomadov i ih

dvihzenia), Osh, 24–25.

ABDULLAEV, K. 1999. ‘New Archaeological Discoveries in Nothern Bactria’, Circle of Inner Asian

Art Newsletter, 10, 7–9.

ABDULLAEV, K. 2001. ‘La localisation de la capitale des Yuezhi’. In P. Leriche et al. (eds), La

Bactriane au carrefour des routes et des civilisations de l’Asie central (Actes du colloque de Termez

1997), Paris, 197–214.

BACHHOFER, L. 1941. ‘On the Greeks and Sakas in India’, Journal of the American Oriental

Society 61, 223–50.

BAILEY, H.W. 1985. Khotanese texts, VII (Indo-Scythian Studies), Cambridge.

BARKOVA, L. L. 1978. ‘Kurgan Shibe i voprosy ego datirovki’, ASGE 19, 37–44.

BARKOVA, L. L. 1979. ‘Pogrebenie Koney v kurgane Shibe’, ASGE 20, 55–65.

�96

Kazim Abdullaev

BARKOVA, L. L. 1980. ‘Kurgan Shibe: Predmety material’noy kul’tury iz pograbal’noy kamery’,

ASGE, 21, 23–31.

BELYAEVA, T. 1978. ‘Ziloj dom bogatogo gorozanina’. In G. A. Pugachenkova, E. V. Rtveladze et al.,

Dal’verzintepa— kushansky gorod na juge Uzbekistana, 33–7.

BERNARD, P. 1987. ‘Les nomades conquerants de l’Empire greco-bactrien. Reflection sur leur

identite et ethnique et culturele’, CRAI, 758–68.

BERNARD, P. & ABDULLAEV, K. 1997. ‘Nomady na granitse Bactry. K voprosu ob etnicheskoy

identificatsy (Nomads on the border of Bactria —on the question of ethnic identification)’, RA,

1, 68–86.

BERNSHTAM, A. N. 1952. ‘Istoriko-arkheologicheskie ocherki Tian Shanya i Pamiro-Alaya’, MIA,

26.

BICHURIN, N. J. 1950. Sobranie svedeniy o narodah obitavshih v Sredney Azy v drevnei vremena, 2

volumes, Moscow-Leningrad.

BOPEARACHCHI, O. 1990. ‘Podrazhaniya monetam Evtidema I i data nezavisimosti Sogdiany’,

Kul’tura drevnego i srednevekovogo Samarkanda i istoricheskie svyazi Sogda, Tashkent, 30–1.

BORISOV, A. Y. 1963. ‘Dva iranskih reznyh kamnya Samarkandskogo muzeya’, Epigraphika

Vostoka, XV, 51–5.

BOROVKOVA, L. A. 1989. ‘Zapad Tsentral’noy Azy vo II v. n.e.–VII v. n.e.’, Istoriko-geografichesky

obzor po drevne-kitayskim istochnikam, Moscow.

DAFFINA, P. 1967. L’immigrazione dei Saka nella Drangiana, Roma.

FYODOROV-DAVYDOV, G. A., VAINER, I. S. & MUHAMADIEV, A. G. 1960. ‘Arkheologicheskie

issledovania Tsarevskogo gorodischa (Novyj Saray) v 1959–1960 gg.’, Povolzh’e v srednie veka,

Moscow.

GRUM-GRJIMAYLO, G. E. 1928. Pochemu kitaytsy izobrajayut demonov ryjevolosymi, St

Petersburg.

GULYAMOV, Y. G., ISLAMOV, U. & ASKAROV, A. 1966. Pervobytnaya kul’tura i vozniknovenie

oroshaemogo zemledeliya v nizov’yah Zarafshana, Tashkent.

HALOUN, G. 1937. ‘Zur Ue-tsi-Frage’, ZDMG, 91, 243–318.

IVANITSKI, I. D. & INEVATKINA O. N. 1988. ‘Raskopki kurgana Sirlibaytepe’, Istoria material’noy kul’tury Uzbekistana, 22, 44–59.

KABANOV, S. K. 1977. Nakhsheb na rubezhe drevnosti i srednevekov’ya (III–VII vv.), Tashkent.

KARLGREN, B. 1957. Grammata Serica Recensa, Stockholm.

KIBIROV, A. K. 1979. ‘Arkheologicheskie raboty v Tsentral’nom Tyan Shane 1953–1955’, TKAEE 2,

107–23.

KOSHELENKO, G. A. (ed.) 1985. Arkheologia SSSR—Drevneyshie gosudarstva Kavkaza i Sredney

Azy, Moscow.

KOZHOMBERDYEV, I. K. 1975. ‘Saki Kemen’Tyube’, Stranitsy istory i material’noy kul’tury

Kirgizstana, Frunze, 174–8.

KUSHAEV, G. A. 1963. ‘Kul’tura usuney pravoberezhia reki Ili (III do n.e.–III v. n.e.)’. In K. A.

Akishev & G. A. Kushaev, Drevnyaya kul’tura sakov i usuney doliny reki Ili, Alma-Ata.

LERICHE, P. 1986. Les remparts d’Ai Khanoum et monuments associés, Paris,

LITVINSKY, B. A. 1972. Kurgany i kurumy Zapadnoy Fergany, Moscow.

LU ENGUO 2002. ‘The Podboy Burials found in Xinjiang and the Remains of the Yuezhi’, CIAA,

15, 21–2.

MALEINA, A. I. (translator) 1993. Plano Karpini i Giyom de Rubruk. Putishestviya v vostochnye

strany, Almaty.

�NOMAD MIGRATION IN CENTRAL ASIA

97

MANDEL’SHTAM, A. M. 1963. ‘Nekotorye novye dannye opamyatnikah kochevogo naselenia

yuzhnogo Turkmenistana v antichnuyu epohu’, IAN Turk SSR (Seria obschestvennyh nauk), 2,

126–37.

MANDEL’SHTAM, A. M. 1966. Kochevniki na puti v Indiyu, Moscow.

MANDEL’SHTAM, A. M. 1968. ‘Pamyatniki epohi bronzy v Yuzhnom Tadjikistane’, MIA, 145.

MANDEL’SHTAM, A. M. 1974. ‘Proishozhdenie i rannyaya istoria kushan v svete arheologicheskih

dannyh’. In Tsentral’naya Azia v Kushanskuyu epohu, 1, Moscow, 190–7.

MANDEL’SHTAM, A. M. 1975. Pamyatniki kochevnikov kushanskogo vremeni v severnoy Baktry,

Leningrad.

MANDEL’SHTAM, A. M. 1983. ‘Zametki ob arheologicheskih pamyatnikax usuney’, Kul’tura i

iskusstvo Kirgizy. Tezisy dokladov vsesoyuznoy nauchnoy konferentsy, Leningrad, 47–8.

MASSON, M. E. 1973. Stolichnye goroda v oblasti nozov’ev Kashkadar’i s drevneyshih vremen, Tashkent.

MAYDAR, D. 1971. Arkhitectura i gradostroitel’stvo Mongoly, Moscow.

MITCHINER, M. 1976. Indo-Greek and Indo-Scythian Coinage, 9 volumes, London.

MOSHKOVA, M. G. (ed.) 1992. Stepnaya polosa Aziatskoy chasti SSSR v skifosarmatskoe vremya,

Arkheologia SSSR, Moscow.

NARAIN, A. K. 1957. The Indo-Greeks, Oxford.

OBEL’CHENKO, O. V. 1961. ‘Lyavandaksky mogil’nik’, IMKU, 2, 173–6.

OBEL’CHENKO, O. V. 1992. Kul’tura antichnogo Sogda. Po arheologicheskim dannym VII v. do

n.e.–VII v. n.e, Moscow.

PIDAEV, Sh. 1987. ‘Stratigrafia gorodischa Starogo Termeza v svete novyh raskopok’. In Gorodskaya

kul’tura Sogda i Baktry-Toharistana v antichnuyu i rannesrednevekovuyu epohi, Tashkent.

PUGACHENKOVA, G. A. 1966. Khalchayan, Tashkent.

PUGACHENKOVA G. A. 1975. Skul’ptura Khalchayana, Moscow.

PUGACHENKOVA, G. A. 1989. Drevnosti Miankalya, Tashkent.

PULLEYBLANK, E. G. 1966. ‘Chinese and Indo-Europeans’, JRAS, 9–39.

PULLEYBLANK E. G. 1970. ‘The Wusun and Saka and Yueh-Chih Migration’, BSOAS, 33,

154–60.

RTVELADZE E. & PIDAEV Sh. 1981. Katalogue monet iz Yujnogo Uzbekistana, Tashkent.

SARIANIDI, V. I. 1985. Bactrian Gold— From the Excavations of the Tillya-tepe Necropolis in

Northern Afghanistan, Leningrad.

SARIANIDI, V. I. & KOSHELENKO, G. A. 1982. ‘Monety iz raskopok nekropoya, raspolozhennogo

na gorodishche Tillya-tepe’. In Drevnyaya Indiya—Istoriko-kul’turnye svjazi, Moscow, 307–18.

SCHEPETIL’NIKOV, N. M. 1960. Arkhitektura Mongoly. Moscow.

SOROKIN, S. S. 1954. ‘Nekotorye voprosy proishozhdenia keramiki katakombnyh mogil Fergany’,

Sovetskaya Arkheologiya, 20, 131–47.

SOROKIN, S. S. 1956. ‘O datirovke i tolkovany Kenkol’skogo mogil’nika’, KSIIMK, 64, 3–14.

TOLSTOV, S. P. 1948. Drevniy Khorezm, Moscow.

TUREBEKOV, M. 1979. ‘Arkheologicheskoe izuchenie oboronitel’nyh sooruzheniy gorodischa

Kalai-Zahoki-Maron’, IMKU, 15, 68–75.

TUREBEKOV, M. 1981. Oboronitel’nye sooruzhenia drevnih gorodov Sogda (VII–VI vv. do n.e. –VII

v. n.e. (unpublished dissertation), Moscow.

TURGUNOV, B. A. 1973. ‘K izucheniyu Airtama’. In Iz istory antichnoy kul’tury Uzbekistana,

Tashkent, 52–77.

VIKTOROVA, L. L. 1980. Mongoly — Proishozhdenie naroda i istoki kul’tury, Moscow.

�98

Kazim Abdullaev

VOEVODSKY, M. V. & GRYAZNOV M. P. 1938. ‘U-sun’sky mogil’nik na territory Kirgizskoy SSR:

K istory u-suney’, VDI, 3, 162–79.

VON GUTSCHMIDT, A. 1888. Geschichte Irans, Berlin.

ZADNEPROVSKY, Y. A. 1960. ‘Arheologicheskie raboty v yuzhnoy Kirgizy v 1957 g’, KSIIMK, 78.

ZADNEPROVSKY, Y. A. 1997a. Review of Borovkova 1989, Drevnei nomady Tsentral’noy Azy, St.

Petersburg, 65–73.

ZADNEPROVSKY, Y. A. 1997b. ‘Puti migratsy Yuechzhey po novym arheologicheskim dannym’. In

Drevnei nomady Tsentral’noy Azy, St. Petersburg, 74–9.

ZEYMAL’, E. V. 1983. Drevnei Monety Tadzhikistan, Dushanbe.

�

Kazim Abdullaev

Kazim Abdullaev